It was a warm spring day in the eighties that I discovered the piece of art that is Ghibli’s Castle in the Sky. I remember it particularly well because my aunty had come round to cut my hair and I ended up missing a good chunk of the movie, but what I remembered of it stuck with me for about twenty years or so until I found the DVD.

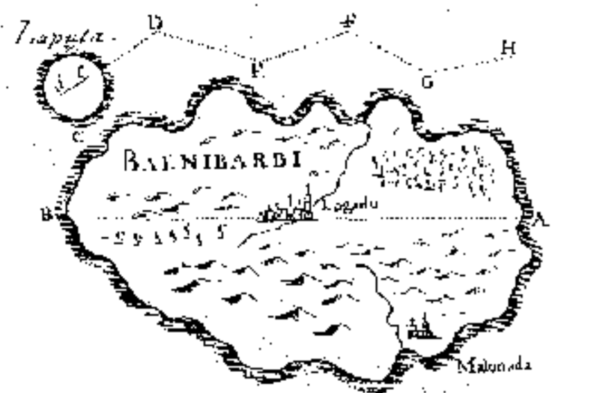

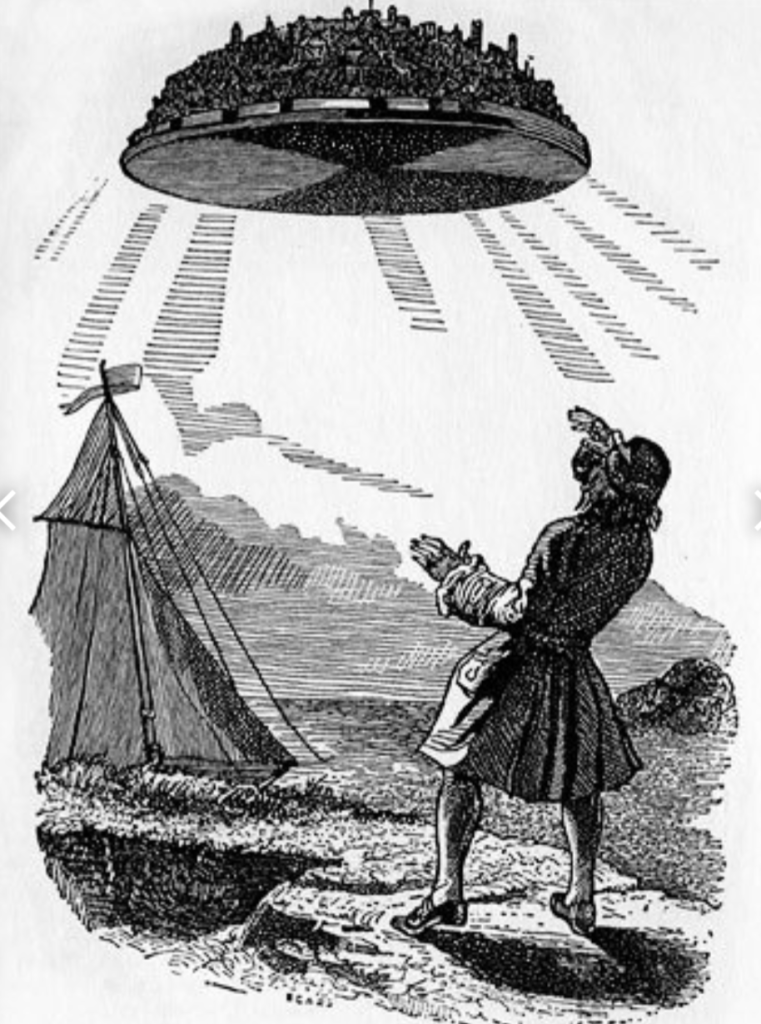

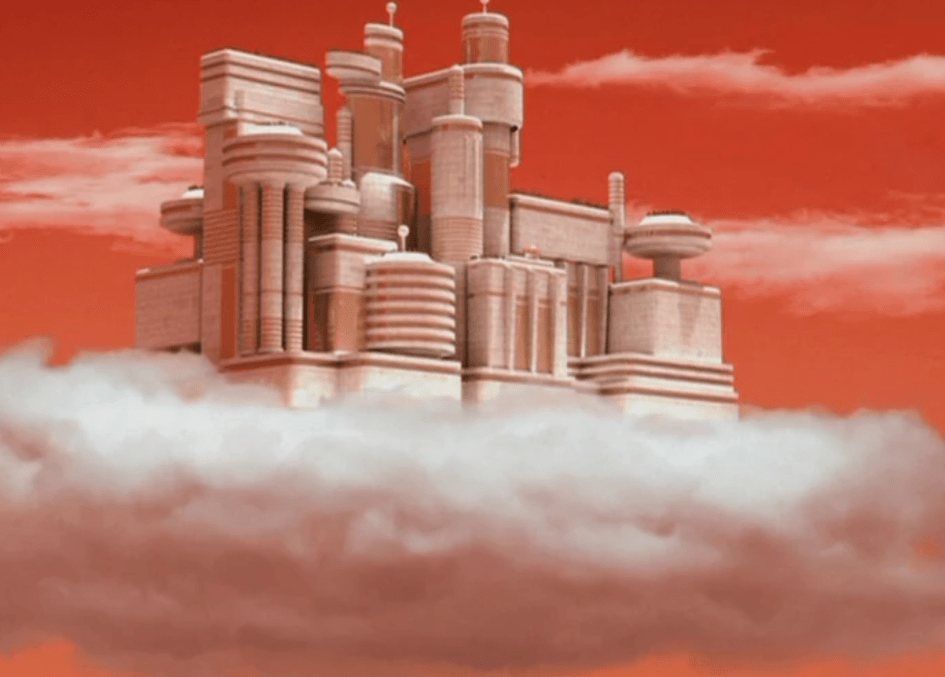

Laputa, Castle in the Sky is an animated movie based loosely on one of the bonkers communities encountered in Jonathan Swift’s classic Gulliver’s Travels. In it, the eponymous Gulliver encounters a madcap people inhabiting a floating castle, directing it with the magnetism of core load stone.

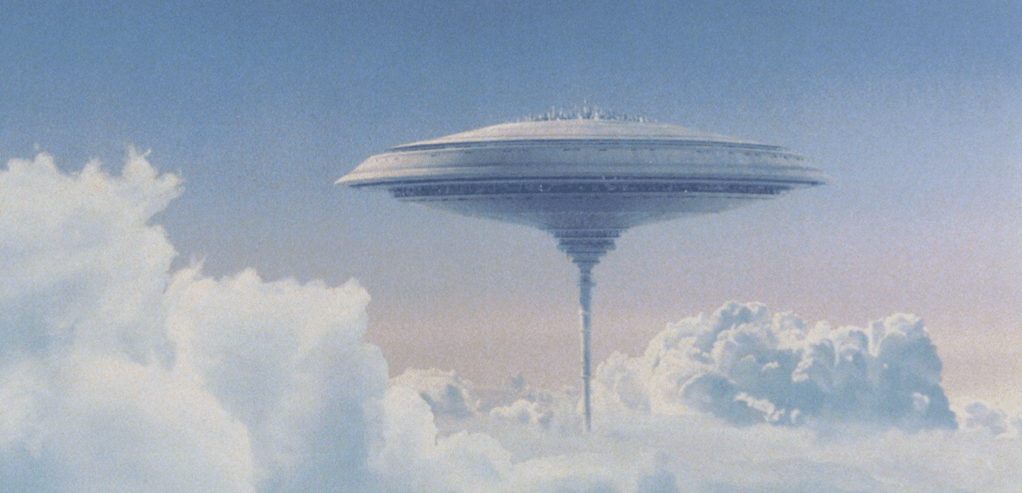

Cloud castles do hold a certain fascination in our civilisation, and they crop up time and time again in both our folk lore, and modern intellectual properties, from Star Trek to Star Wars and everything in between, there are cloud castles or cloud cities.

But fascinating as floating castles are, that isn’t the true appeal of the movie. The location of the story isn’t specified, there is no indication of when this takes place but it feels like the early twentieth century in Europe. Steam power and flat caps, but this isn’t a historical piece. There is powered flight beyond what we have, massive airships and insect inspired winged single seat craft.

When and where this is, we do not know, but there seems to have been a great destructive war and the people that are left are just getting on with it. The backdrop is that of post industrial decline. Crumbling brick buildings, factories, furnaces, mines. It’s a nostalgic post golden-age golden age. That’s the only way I can describe it.

The lives of the characters we meet look tough. What they have is old and broken, they mend and make do, and they work hard to survive in a harsh barren mountainous area. But they laugh and they smile and make the best of it. Except of course for the antagonists. There are forces in this world, above the lower orders, with agendas and schemes that intersect with the sleepy mountain town when a stranger falls out of the sky, and when outsiders arrive in the town to find her, the residents are not to be pushed around.

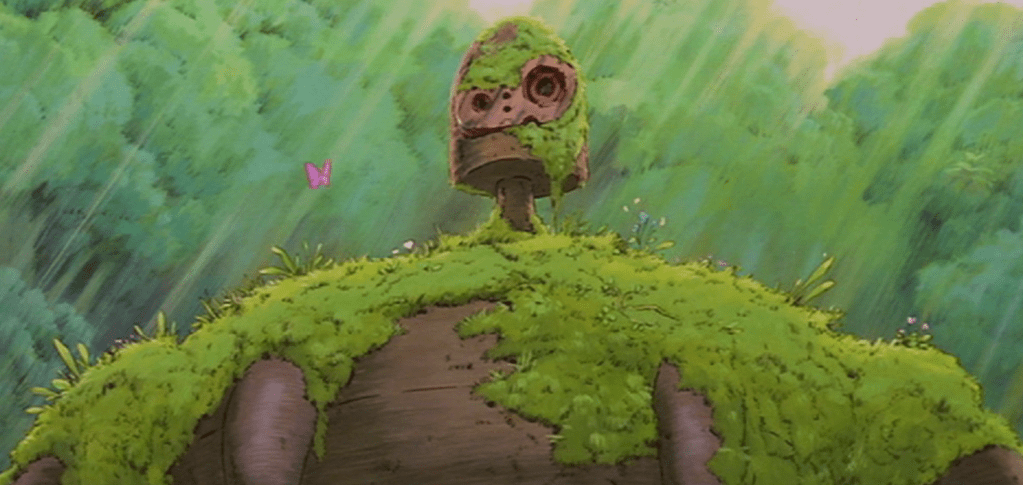

It’s a golden age of freedom and innocence, of kinship, community, and honest work, but all around there are clues to a golden age of abundance that has since been lost, the mythical floating island, and their terrible weapons of war, the mysterious giant robots that are dotted around the countryside, rusting, overgrown, returning to the Earth.

There is something both alluring and distantly familiar about the world presented here. I’m reminded of the eighties, when the mines closed, and the steel works, and the factories were left to decay and collapse, the dismantled railways overgrown, like the giant robots, and left to return to nature.

There is something unsettling about living in this age of uncertain abundance. That saying, “easy come easy go”, it is usually said so casually by some vagabond or scrounger type character, but it’s actually a warning. That which we gain with ease, we can lose with ease. I can’t deny the convenience of being able to go to the supermarket and buying an oven ready chicken, but I’m entirely reliant on others, a chain of others, to ensure that there is a chicken there for me to buy. That situation seems way more precarious than the self reliance of a small community living atop a literal precipice. The image of self reliance against adversity is as compelling as it is romantic.

I can’t help but feel that there is a message in this movie, that we have perhaps missed something. A great civilisation of massive power and achievements has crumbled away, and no one remembers it, no one mourns it or even speaks its name, and no one seems the worse for it. That is not to say I’d like to see a collapse of our civilisation, by any means, but a bit more self reliance would do us all the world of good, but I worry we’ve lost the capacity for that. Can’t exactly keep chickens in a one bedroom flat, but I suppose that’s what is romantic about it, it’s unrealistic.

I can’t end this post without mentioning the trains though. There is a wonderful steam railway running through the mountains, carrying coals and wares, and of course the military for its unknown manoeuvres. I can’t help but notice the similarity of the locomotive number 7, to another number 7. Someone once said that there is no such thing as a coincidence, only the illusion of coincidence.