The Old Pit Lane

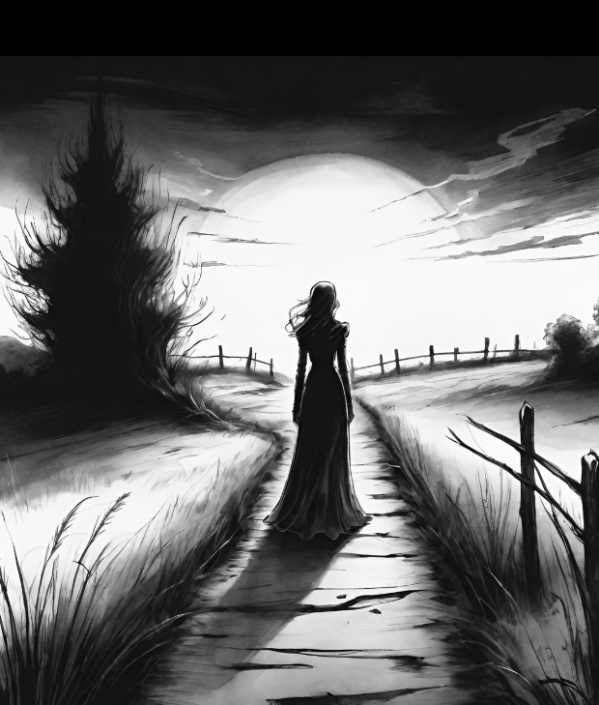

This was back in the Eighties while I was cataloguing the tales of the White Lady, one of England’s more prolific spectres, and it was my last trip of the project that brought me to Thurnscoe in South Yorkshire.

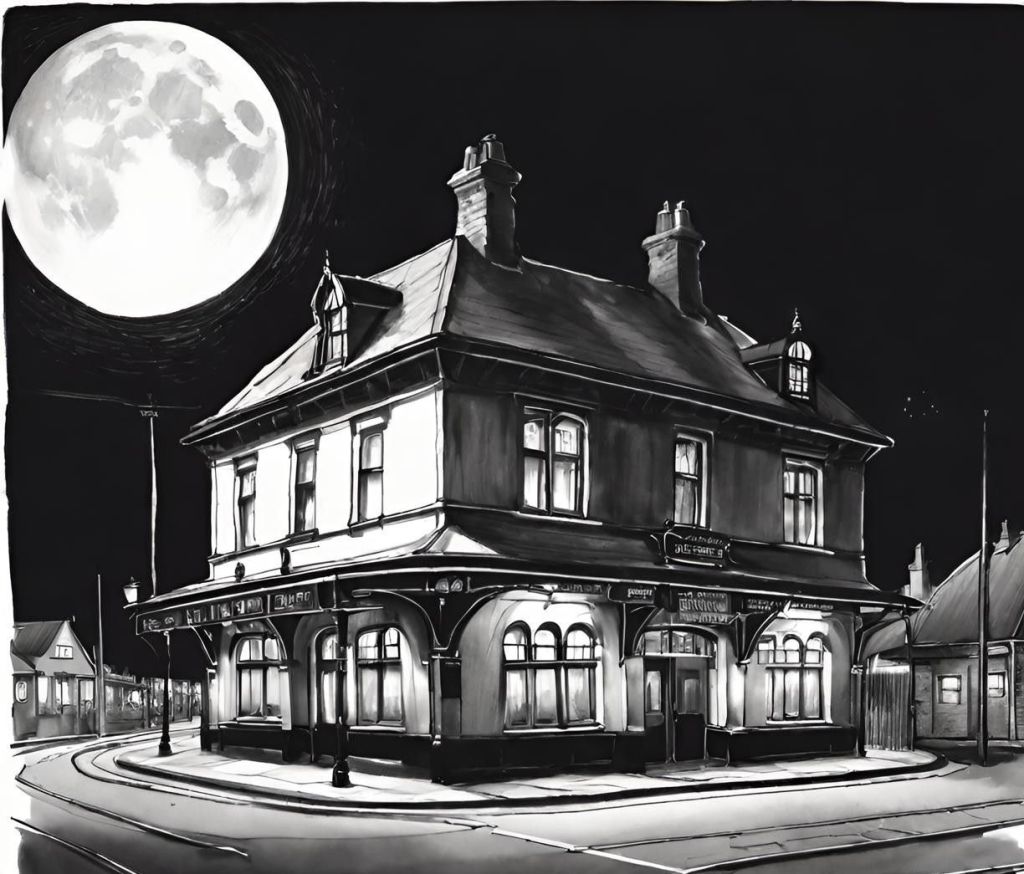

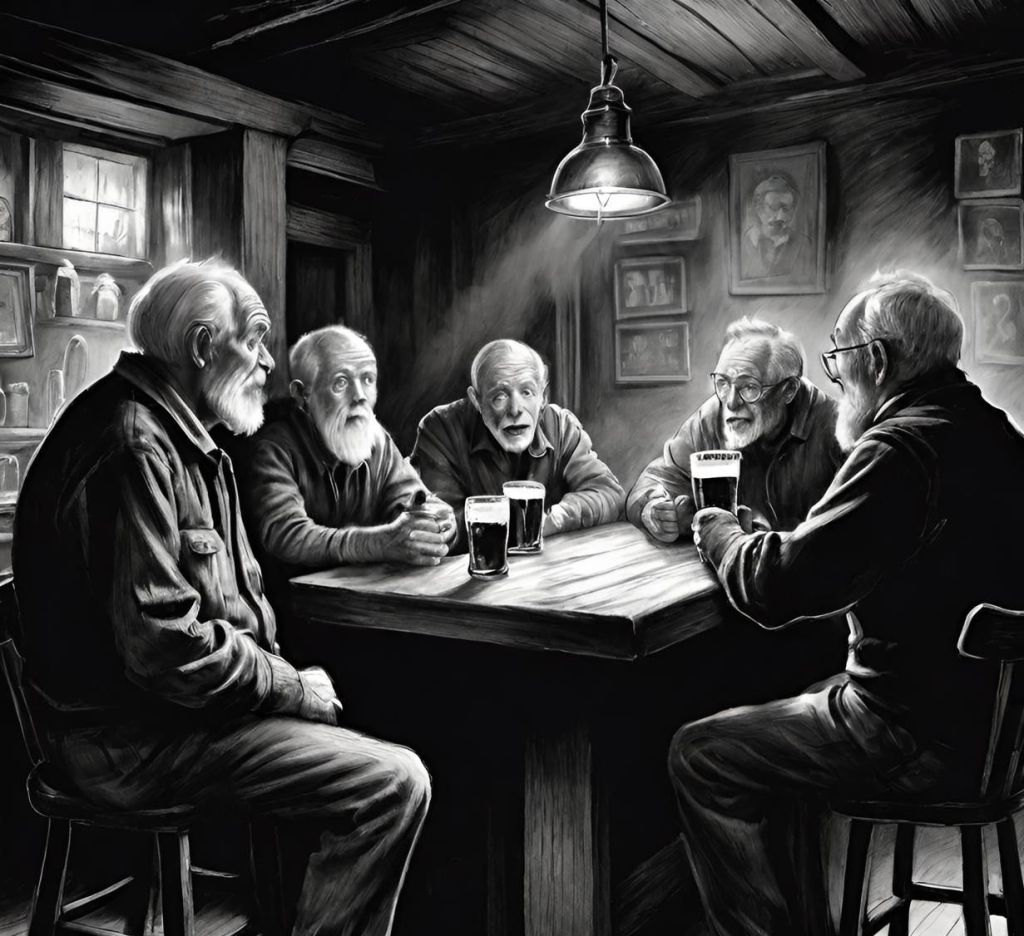

I had found lodgings at the Station Hotel, a pub with seldom used guest rooms run by a feisty middle aged scots woman. What she lacked in height she atoned with fiest and she’d very kindly offered to introduce me to some of the locals that might be of help. As luck would have it, they were all regulars at her bar; an old fashioned working man’s pub, with over bright lighting, threadbare carpet and nicotine stained walls. The tobacco smoke hung thick above the customers, thick as fog, exacerbating my asthma. I couldn’t stay there long.

Everyone I spoke to knew of a different story about the White Lady, where to see her, what she looked like, who she might have been in life. I suppose that made it the oddest thing. While the stories differed, everyone had one. Though few people claimed to have seen her themselves, everyone knew someone that had.

“Hit by a train she was” one of them would say, “taking a short cut back in the 1900s, she stopped for one train but got struck by another, her body was thrown down on to the path with such force that she never knew she’d died, now here she stuck forever looking for a way off the path and back to her home…”

“Raped she was” Another, older, man told me. “Back in the twenties, everyone heard about it. Poor young thing taking a short cut over the heaps…Now her spirit lingers up there, warning travellers to take care and never travel alone…”

“Don’t listen to them” yet another would say, “It was Marian Spitch, wife of Tommy Spitch, she killed herself after the pit collapse back in 1947”

“No no no, they’re all wrong” A haggard old man told me, “She been walking that path long before the pits came. These were milking pastures back in the day, and the white lady was a cow girl, dressed in a white apron…”

The night went on this way, everyone had a theory on who she was, and my note book grew fat with anecdotes, but I had spoken to almost all of the patrons before anyone confessed to having seen her themselves. But maybe that was the alcohol loosening the tongues of the later evening that drew forth the crazier tales.

“I saw her” A younger man, in his twenties, said, “up on the tops. I was walking up Goldthorpe way when it started to rain. Sile it down it did. I was struggling to cover my eyes and keep my cig lit, and I ended up tripping and stumbling on the grass. I got up again and carried on, but I tripped again on a slab or stone or something. When I got up, she was there, stood in front of me, I felt her hand on my shoulder, like ice”

“What did she look like?” I asked him, I was glad of the first hint of a real encounter that entire evening.

“Just white” he said, “I had rain in my eyes and it was dark, couldn’t really make owt out”

“You must have seen something”

“Yeah, she had a face, nose and eyes and stuff, but soon as it twigged what it was, or who, I was outta there. Turned right round, back on the path. I ran home without another glance.”

“Was she old? Young?”

“I said I couldn’t tell, it were dark, shouldn’t have seen her at all up there. That’s how I know she was a ghost; she had this glow about her”.

“Did she say anything?”

“As it appens, but it were like the wind shouting at me, ‘go back she said’, and I did, never ran so fast in my life”

“What else do you remember?”

“That’s about it really, but she did remind me of me mam, telling me off”

“Could you show me where it happened?”

The coloured drained from his face.

“You’ll not see Nige up on that hill in a month of Sundays” An older guy piped up”

“Chicken he is” Another said. Nigel looked agitated as the whole pub burst in to laughter.

“You didn’t see what I saw” He said.

“That why you turned down the council job intit Nige” The old man piped up again before turning to me. “Fifty a week he was offered to go up there and clear out the trees for the new lights”

“Fifty quid, that was a lot back then” I said.

“It’s a lot now” One of the rougher looking men said, “What you on about?”

I didn’t answer him. This was the height of Thatcher’s recession, jobs were few and far, and this was a community with its heart torn out. Tensions were high, and I was already too aware that mine was the only jacket with leather elbow patches. Everyone else wore Parkers, jeans or shell suits with trainers, and looked just a little under nourished.

“Is that pit still open?” I asked no one in particular, “I was sure I saw trains coming out of there?”

“It’s on run down now, clearing out stocks and decommissioning, all us lads from the shafts are now on the dole”

“I’m sorry” I said, “I didn’t realise, “When I wandered round the village earlier, the whole site was alive”

“It’ll all be gone soon, 100 years gone in a wink…”

The mood was changing, and I wanted to get back on topic. Eventually, I did manage to coax a small map out of Nige with enough detail to convince me I would find the place.

—

I woke the next day to a foul head, the strong ales and interesting quality storage had left me feeling seriously hung over. My very best effort saw me leave the hotel at just after midday; I decided to skip the beef dripping chips that Beryl offered for breakfast.

It was a warm day for October, if a little blustery at times, but I was adamant that I would at least find the spot as directed by Nige. Ghosts of course have a tendency to only present themselves in darkness, and when there is enough ambiguity in its presence, but I wanted to at least give it a chance to appear.

The old pit lane, as it was called, runs between the two mining villages of Thurnscoe and Goldthorpe, over the old pit head, along the side of slagheap.

To reach the lane, one had to walk toward the colliery itself, about half a mile from the Station Hotel, past a long line of dreary old blue brick terraced houses, the likes of which might have been torn down in the fifties. Eventually, I came to a junction, where vehicles could access the site from the main road, and the pavement would follow the road down toward a number of low bridges that carried the rails serving the pit overhead. Despite the diggers and lorries in the main complex, there was an eerie silence about the place that served to exaggerate the already intense sense of abandonment and disrepair about the place.

There were gaps in fences, pot holes and weeds abound the old tarmac pathway, and panels missing from the street lamps exposed live wires to the elements.

Approaching the first of the over bridges, beneath which the narrow path veered to the right, the blue brick bridge supports obscured the route ahead, and the tip tap sound of foot falls, muffled voices and children’s laughter, distorted by the sound funnelling effect of the bridges preceded the passage of two young girls and their push chairs.

A light on the underside of the bridge flickered on and off and beams of light shone through between the girders above, while drops of water dripped rhythmically, seeping through the tracks above like a lethargic shower.

From that darkness, the pathway broke out in to daylight and climbed steeply up to the height of the track on the bridges before levelling off for a little. From here I could see coal wagons in the marshalling yard and the faded yellow skeletal form of an abandoned Coal Board locomotive, stripped of parts and rotting at the edge; and running parallel to the tracks, an enormous floodlight tower, rested where it had been felled and lay waiting its final fate.

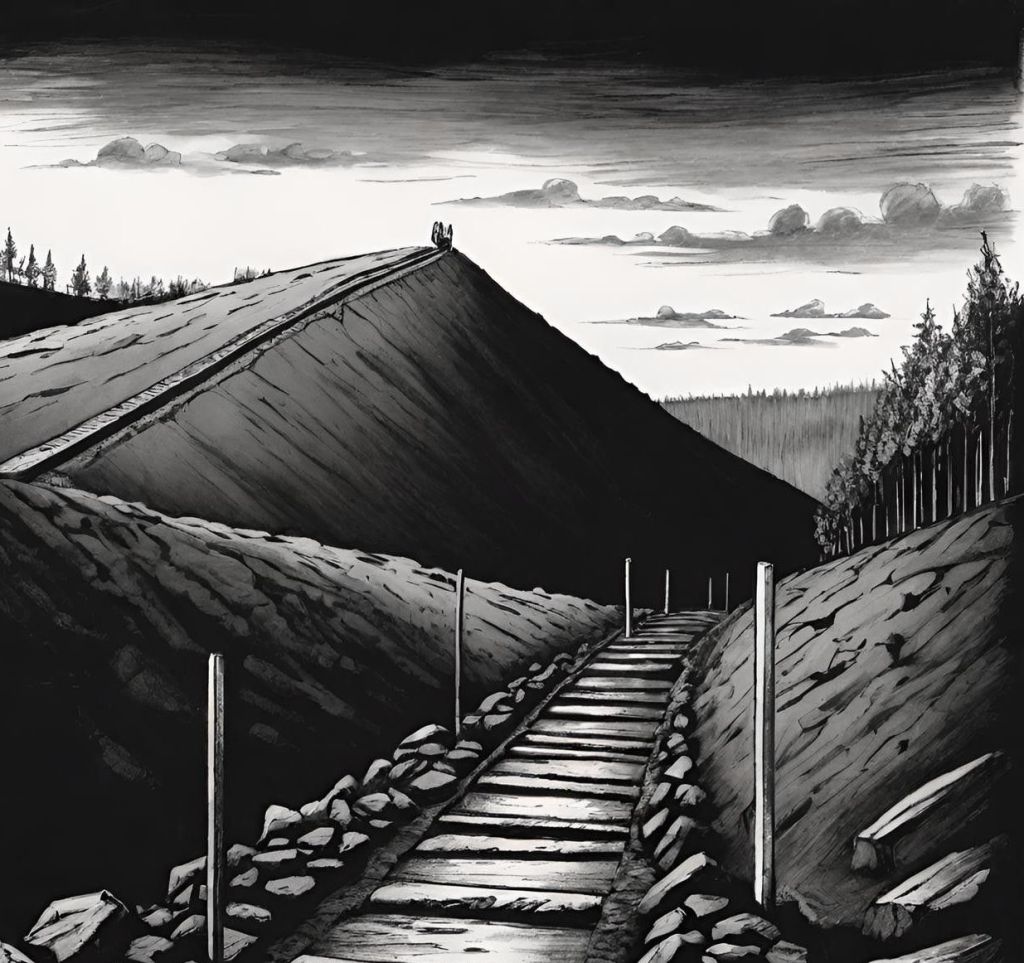

Onward the path began to climb in a long steady uniform line up the hill, bisecting the huge manmade mountain that had grown up over the years from the displaced material excavated from the mine.

The ascent itself was gentle, but relentless, and took a full fifteen minutes to reach the summit, but the view was reward enough. The surrounding countryside was beautiful, gentle slopes punctuated by woods and spires rolling in to the peaks of the Pennines, but in the foreground, a sprawling mass of black industry scared the landscape.

Sloping east from the summit of the path, the hill rose for a further five yards or so, though this was fenced off with a high metal chain link fence, and I overcame the usual impulse to trespass; all of the stories focussed on the path itself, so that’s where I would look.

I pictured Nige at home; laughing at the naïve southerner following a wild goose chase as I looked around the area he had directed me. There were no distinguishing features on the path, or along its edges; just grassy scrub, the fence, and the occasional tree.

It was easy to imagine, however, why these stories might arise. The whole ascent is quite isolating, even with the full daytime foot traffic, all of which smiled, or nodded, or greeted me with a firm Yorkshire Ay’up. But it was the unearthly stillness that seemed the creepiest. A hill like this should be windy, but the bulk of the hill seemed to protect this side from the prevailing easterly wind, and no sounds carried from the village or the pit below. I could see diggers, bull dozers and tipper trucks below clearing away the abandoned buildings, but there was no sound of this.

This I think was enough to settle my curiosity. I have come across few places so genuinely calm and incongruently spiritual as this one. It was too much to expect to actually see a ghost as well.

—

I returned to the B&B with a clearer head and a resolved appetite where I was fed a monumental serving of homemade shepherd’s pie, (made with beef mince I might add) and baked beans for some reason, and mushy peas, and a slice of buttered white bread. I coukd not recollect a time I had been so well fed and I decided to stay another night and try out the path under darkness, just to test my luck.

Once night fell, I dressed warmly and made sure I was kitted out with my ghost recording kit. It was nothing as fancy as the Ghost Busters might have; just a Dictaphone, a camera with flash, a torch and my homemade mobile barometer. Intrepidly, I stepped out into the night, fearful more of the disenchanted youths that loitered by the market stalls and the entrance to the unmanned Railway Station that might give me some grief than the ghost, but this evening was unusually quiet; it must have been a school night.

I retraced my steps from earlier that day through the deserted streets. It was blustery as before, but warm, and the low clouds passed swiftly above, illuminated by the deep orange glow of the argon street lights; the air itself heavy with the acrid weight of a thousand open coal fires.

Passing beneath those bridges was daunting. One could imagine an ambush, were one minded that way. A tale of ghosts on paths, a trap irresistible to the feeble southerner on his quest for knowledge, the men of the Working Man’s Club would lay in wait for their prey. I imagined.

I entered the passage that led down to the bridges, and again, they echoed with the chatter of others traversing the path, an ambush? The scent of old spice and Brylcreem preceded them, just moments before a small group of seniors emerged from the bridge, suited and booted, ready for their night at the WMC.

I passed the set of bridges without incident and began the accent. I rose up above the village, I could see the town illuminated beneath, but the old colliery works were shrouded in night. It must have been quite the sight ten years ago. The floodlight towers, now strewn across the marshalling yard, would have bathed the whole complex in a bright white light, and trains would be heard rattling around all times of day. For the villagers though, this was an unwelcome peace.

A brisk walk brought me to the summit after about ten minutes, and I allowed myself a break to catch my breath. Occasionally, I noticed, the wind must have dropped or changed direction, and the eerie silence would be replaced by the sound of traffic, a train passing on the railway below, or a bus toiling its way out of the valley, but as soon as it began, it would drop off again, and the hill returned to silence.

Occasionally though, I could hear, just at the edge of my hearing, the sound of children playing. There was a play area at the bottom of the hill, across the road from the start of the path, but this was in darkness too, and the children should be long in bed. Almost certainly another effect of the odd microclimate here, but then I noticed the lights on the ground and my imagination ran away with me.

Willow the wisp, marsh lights or corpse lights, as they are sometimes known. Tiny flames believed by some to spirits of children, believed by others to be nothing more than combustible gases seeping through the earth. Either way; this was only the second time I had seen such things, and the first time I had done so with a camera to hand.

I took out my SLR and began snapping, two frames at a time, one with flash, the other without. The strange little dancing lights took on a life of their own, and it was hard to even speculate on a rational explanation for them as again, I heard the muffled sound of children laughing, and it grew grow louder as I followed the lights on to the damp grass.

This was amazing, and far more than I could have hoped for, if not a ghost itself, then a rational explanation for the stories, and with pictures to boot. I even remember laughing out loud, scarcely noticing that the ground beneath me had become muddier, wetter, and a little spongy. Not until I felt something on my leg.

I froze on the spot, as the terror dawned on me. My foot was stuck in the mud, it was as if a hand gripped tightly to my ankle, and it took all of my strength, and the sacrifice of a boot, to break free, and when I did, I was so off balance that I found myself face down and struggling against the mud as each attempt to find my footing felt like another hand grappling with me, pulling me down. Panic began to set in.

Darkness surrounded me, but for the silhouette of my own arms flailing against the orange sky above as I grappled with some unknown attacker. I had strayed from the path and I would need to find solid ground if I was to escape the cold clutches of the treacherous heap.

Again, I felt an unseen hand on my ankle, and my leg sank knee deep into the mud. The struggle was exhausting, and the fight had disorientated me. It was all I could do to free my leg and roll on to my back, where I awaited my fate. I expected a final blow to finish me off, dragging me to muddy depths, but there was silence. The battle seemed to be over.

I lay there, quietly gathering my thoughts. Perhaps whatever foul creature had attacked me now thought I was gone, or dead, perhaps it too was blind and waited on my movements before it could attack again. Maybe it had gone for back up. Whatever the truth, I could not spend the night here. Already, I felt the mud around me rising, who knew how deep I might sink.

I cautiously looked around, unwilling to disturb the mud, but saw no distinguishing features against the turbulent sky above. Raising my head, I saw no sign of the path. Thoughts of my mortality ran through my mind, what would the papers say? Would my body even be found?

As the last of my hopes sank with my spirits, I caught sight of something to my left just in the corner of my eye. A figure in white stood nearby, but only when I looked away. Like the Seven Sisters in the northern sky that fade from view when directly looked upon; this figure too vanished when looked at. So turning my gaze to the right, the figure again appeared to my left. Was this the white lady? I remembered that she was always seen on the path in the stories, and whether she was the ghost, or a reflection of light from a road below, salvation was that way.

I tried to find my feet, but this only caused the mud to rise higher. A new tactic was required, and anything was worth a try. I tried rolling on to my front. This too was difficult, as the mud seemed to have moulded itself about my hulk, but eventually, with the last of my strength I managed it, and once moving, I burned my second wind to keep my momentum, rolling my way to the left, back toward the grassy verge and the refuge it offered. Exhausted, but on solid ground, I rested just long enough to find my strength for the hobble back to the pub.

—-

Almost two hours later, I arrived back at the Station Hotel, exhausted and barefooted on one side. Having passed no fewer than five people on the way, all of which greeted me politely, but none offered help. I pushed open the double doors and hobbled inside where the iridescent lamps brought my plight into deep relief.

“Goodness me” The landlady shouted from the bar, “Where the devil have you been?”

“Back up the pit lane” I told her,” looking for your white lady.”

“Did you find her” One of the old punters cried out.

“I think I did” I said, but I was drowned out by another

“Looks like you been rolling in the slag up there” one of the others warned, “Want to be careful up there”

“You could have died up there, what on earth is a grown man like you doing trespassing on the heaps” Beryl came round the bar and took me in to her care. “Let’s get you sorted upstairs”

“The heaps?” I said

“Yes” Beryl said, “now let’s get you out of these filthy black clothes”

I hadn’t registered how I looked. My suede jacket and corduroy pants were thick with black wet mud that was now starting to dry to a dull grey at the edges. My face and hair caked too. I must have been quite a sight walking through the village.

“Tracy” Beryl said to one of her staff, bring him a shot of Bells up will you”

I went upstairs to the communal bathroom and tried to the close the door behind me, but was surprised to find Beryl had followed me in.

“Come here love, stand in the bath while you get undressed, don’t want no slag on the floor. There’s a basket here for your dirties…”

She was interrupted by a knock at the door. It was Tracy with my shot of whisky.

“There you go love”, she said, placing the shot glass on the drawers by the bath, “I’ll leave you to it. Come down when you’re ready, I’ll have a steak and kidney pudding waiting down stairs.”

So I had a nice hot relaxing bath and reflected on my experiences, the absolute silence of the place, the laughter, the corpse lights, the unseen hand reaching out of the ground, and then the white lady herself. A lucky escape definitely, but it couldn’t be too good to be true. If only my train wasn’t the next the morning, I so wanted to visit the site again in daylight and gave thought to an early wake up call.

–

Hungry, I tore myself from the bath, put on a pair of jeans and woolly jumper and went back downstairs to the bar area, where, as promised a steak and kidney pudding and a generous portion of chips, peas and gravy were waiting.

“There you go love” Beryl said, handing the hot plate of food to me across the bar. “Get that down you”

I did as I was told and was left in peace to eat my evening meal, but ever aware that I was drawing some attention, and the very instant that my knife and fork hit the empty plate I was surrounded by men, and Beryl, her arms firmly crossed. I began to worry that I had broken some local taboo.

“Do you know how lucky you are not to be dead?” Beryl bleated.

“Bleedin idiot you are!” Another voice croaked from the back. What had I done?

“What did I do?” I begged, unsure what might follow.

“Did you not see the signs?” Beryl said again.

“Or the ruddy fence” someone else laughed out.

“It’s a slag heap up there! It’s like quick sand!”

“Aye, once the slag’s got you, there’s no coming back”

My heart began to pound, I had no idea of the dangers, but they were laid out to me, somewhat painfully and repetitively by the locals, whose concern was only matched by rare opportunity to teach a scholar something new. But things soon settled down, and the usual business of drinking returned to full swing and I was joined again by just Beryl.

“So did you find your ghost?” She said.

“I’m not so sure anymore” I told her. “I saw the marsh lights, but I can explain those, and for a moment, I thought I saw the white lady, leading me out of the mud”

“That’s not all though is it” she said. She could tell I was hiding something, and I confessed about the hand, but the triumph I’d felt before, of overcoming some monstrous being from the underworld, was now just the utter embarrassment at my naivety of all the industrial dangers that surrounded this place. I had simply got my foot stuck in some mud.

Instead of visiting the path again, I quietly gathered my belongings, packed my bags and made a discreet departure the next morning, but I did leave with a promise from Beryl that she would forward a number of newspaper cuttings that she had collected over the years about the ghostly reports in the area.

—–

Six months later, I was making sense of my notes and typing up accounts of my ghostly encounters across the hills and valleys of England. I had looked further into the tales I’d been told and was confident in both my subject matter, and the appeal of my latest book. Where the White Lady of the Old Pit Lane was concerned, I was most ambivalent. I certainly had a creepy encounter, and all of the stories checked out. My meticulous research uncovered several key truths in the myths that haunted the village of Thurnscoe.

Millicent O’Donnell age 17, hit by a train in 1907.

Victoria Connelly, raped and murdered on the Pit Lane in 1927

Marian Spitch, found dead in 1947, drug over dose

Henrietta Swardle, a milker’s Maid, trampled in the 1800s

There was an interesting history here, and maybe one worthy of a more substantial investigation, but I was also ashamed of my behaviour.

By sheer coincidence, it was at the very moment I had decided to drop the case of the White Lady of Old Pit Lane that I was given cause to reconsider. There was a knock at my office door and I opened it to see the college porter holding up a large brown parcel.

“Sign here” he said.

I took the parcel back to my desk and carefully open the letter that was attached with sticky tape to the top.

Dear Doctor Bosthwell,

As promised I have gathered up some of my newspaper cuttings from the local history group and sent copies. What I think will interest you more though is the local news from two weeks ago. In the 70s a young boy went missing, he was last seen following some older boys through Goldthorpe village, but when quizzed they said they hadn’t seen him. The area was searched, including the slag heap where you so foolishly wandered, but no body was ever found. It seems that search wasn’t thorough enough. That whole area is being reclaimed now and the diggers moved in just after you left us. You can guess what they found, and you can read the terrible details in the papers I have included, but what I think you’ll find most interesting is what was found in the boy’s hand. The police won’t release it to me; you’ll have to collect it yourself, but I have included the photograph they gave me…

My hands trembled as the thought of that gruesome struggle came back vividly to mind, and I turned over the enclosed photograph.