It’s funny how becoming a parent changes your life in so many ways. You look in to those brand new eyes, the eyes of a new person, a unique individual, and imagine all the things they have yet to see; the life they have ahead of them.

For the past, however many months it is, all they’ve seen is the pitch blackness of the womb, punctuated by the occasional red glow of a bright light from somewhere beyond penetrating the flesh and in to the womb, so all of this, my face, mommy’s smile, is all new to them. Or at least it, we assume it is.

I’m not really one to believe in reincarnation, I’m not really sure I believe in a God, but when I look in to those deep blue eyes, there is so much more depth, more pain, more joy, more tales to tell than in any of the other eyes that I have ever seen. The things they would tell you if only they had the words.

It is nonsense I know, but when I tore myself from my wife that night, nursing our new born child in that hospital room, I got to thinking of my own life, my childhood, my parents and upbringing. How might his experiences compare to mine, I too was once a tiny new born once, a blank sheet, as it were, what will his first memory be? I remember mine so vividly, and not like it was yesterday, but like it were today, still happening now, like part of me is caught, forever in that moment.

I can’t have been much older than one. My mother always insisted that all of her boys were walking by that age, though I can’t have been any younger. It was the day I was given a first taste of freedom, and my first real reprimand that I recall, though there must have been others before it, for me to have dreaded this one so much.

My parents were very strict on hygiene, and germs and disease, that led to a paranoid over-cleaning of surfaces and the unfortunate over-cooking of food. Maybe this is why I like crunchy vegetables and rare meat so much, in rebellion of my folk, but I knew even then that I must not eat from the floor. That was forbidden.

It was a warm day, must have been August, since that was the month of my birth, and I wasn’t quite walking yet, but I do distinctly remember that this was the first time I was allowed out on to the communal grass to play by myself. To the front of the house was a grassy area where the older kids would play. There were no cars here, just neat little footpaths that meandered between the houses and through the estate. I remember quite clearly for such an early age, the elation of being allowed out by myself, the freedom I had been given, and how I would not disappoint. But I was wrong about all three.

I clambered up the shallow sloped path that led on to the main pathway that served the 1970s traffic-free open plan estate, and remember coming across the small dip in the tarmac. This dip features heavily in my early memories. About a foot across, but only an inch deep, this was where the older kids, and eventually myself, would assemble to play marble tournaments. Or when it had been raining, me and my brothers would race, fighting all the way, to be the first to leap, feet first, in to the puddle, full pelt, and empty the dip of water before the others got there. It was worth the inevitable thick ear.

But anyway, back to the one year old me, alone on the footpath. Dad had definitely closed the door behind me. I was alone, free to do as I pleased, and although I knew not to put things in my mouth, I soon came across the discarded outer wrapper of a packet of Opal Fruits; the ones now branded as Star Burst.

I don’t know what I was thinking, maybe I figured no one would know, but I felt wrong even as I did it. It was like being possessed by one’s own primal instinct. I clutched the litter in my chubby little fingers and raised it to my mouth, but even as I did so, something compelled me to look up. Twisting my back and neck to look up and over my shoulder. My heart sank as I realised that I was not as alone I had believed.

Of course my Father hadn’t let me play out alone, I was a baby, and he was right there, watching me from an upstairs window. I caught just a glimpse of a boiled red face before it disappeared, and before I knew it, I was back indoors.

I can’t say as I remember my punishment, I don’t really remember much else from that age, but this one thing, every detail, down to the Opal Fruits wrapper, is clear enough in my mind that I know the memory is real.

I had the most lucid of dreams too as an infant. Often waking in the night to find my mam sat beside me, often before I’d even realised that I’d even had a nightmare. Usually, it was my two older brothers that had inspired the dream. They teased me rotten, both of them being a fair bit older. I would scream not to be left alone with them as Mam and Dad would get ready for their Friday night out down at the Clog and Hatchet. Bizarrely, though, my brothers would usually manifest themselves as girls in the dream.

One dream in particular has stuck to me to this day. My “sisters” had pinned me down and tickled me so hard that I woke up screaming. I think it scared my Mam that I talked so much about the sisters I never had, and whenever I try to ask her about it later, she said she didn’t recall, or that it I was confused between boys and girls, him and her, he and she, when I was younger, but I know that that wasn’t it. The two older sisters were blonde and had long hair; I can see them now if I think back, tying me the washing line or putting Barbie’s shoes up my nose for their evil amusement.

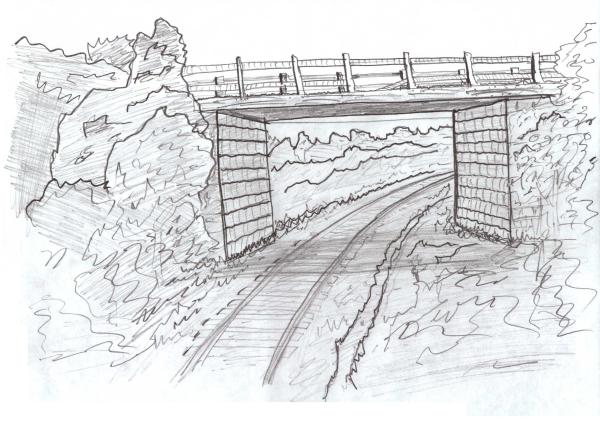

But there was a recurring dream too. On more than one occasion I had this dream that I had fallen off of a railway bridge, often enough that for some time I believed that it had actually happened, especially though, as I never dreamed of the accident directly, just that it had happened, like I had been told about it happening to me. I was usually at school or nursery in the dream, and the teacher would explain why I wasn’t there, that I had fallen, had a terrible bump, and why the children must always stay with their Mummy and Daddy and keep away from the bridge.

I hadn’t thought about this stuff in years but something in Byron’s eyes got me thinking; awakening old memories, my oldest memories in fact. So old that dream and fact and imagination often overlay each other, blurring the lines that should keep them separate. Of the nice dreams that I have had, this one was the nicest. It was about God.

At the edge of the estate was an old ash path that led through the wheat field, over the railway, and then in to the next village where Gran lived. I walked this way so many times with Mam, or Gran, or sometimes both, through those bright yellow fields, which to my knee high stature pretty much formed the horizon, connecting with the soft and fluffy white clouds that sailed silently above in the rich blue sky. It was inevitable that they would find their way in to so many of my earliest dreams and memories.

In the warm breeze, where the wheat crops rippled like waves on a vast yellow sea, and birds cawed cheerfully above, my asthmatic gran would wheeze as she dragged me away from something in the bushes that I had no business prodding. In my dream I would hear laughter and happy music, an assault on the senses, and always I would be drawn to this spot, where it was always sunny, and filling the sky above and down to where the sky met the field, was God. God, as I understood him to be with my innocent young mind. He smiled on me; and a long arm would sweep across the surrounding fields, not beckoning, but welcoming, like an open invitation to enjoy all that I could see. It felt like home, safe.

These dreams stopped by the time I could verbalise them, but that part of the village was always an enormous draw to me; but then I’m sure that the real appeal was a little less ethereal. It was of course the path that led to the train bridge, and what was more attractive to a small boy than the sight of a dirty great big noisy blue diesel locomotive chugging up the hill with a long train of coal hoppers?

My mother must have had the patience of an angel to stand and wait there on the bridge, in all weather, in the hope that something would use the line soon. But it was hardly a Mainline, and hours at a time could pass before a train would come by. I loved to see Gran, with her chip butties and jam rolls, but not until I’d seen a train or two. I image Byron will be very much the same.

It wasn’t just the trains either, that drew me to the bridge. Down the line was another bridge, just close enough, on a clear day to see people crossing it. Sometimes they too would stop and look up the line, and I would wave to them, and they would wave back. Another little boy and his Mam perhaps, just like me, waiting for trains to pass beneath.

I was fascinated by that other bridge and I kept nagging my Mam to take me there, but she would always say no, that it was too far, or we don’t have time; but as a child I was as resourceful as I was persistent, and eventually persuaded her that we needed to walk down the path that ran parallel to the track and in to the village. I was certain that we would cross another footpath that would lead to the other bridge.

The path ran straight and hugged the side of the railway that lay in the cutting to the left. I would have been most disappointed had a train passed now as it would have been out of sight. It wasn’t long though, before the path began to descend, and soon we were level with the track. There was a gap in the hedges here and I could see through to the rails. The rail was now at eye level. It would have to rise again soon to provide another crossing, but it didn’t. The path continued to descend, and dropped through a hedge row and in to a ginnel flanked by high fences before emerging on to the main High Street of our village, next to the low bridge that took the road beneath the railway and out of town.

I couldn’t understand it. I thought I had the whole spatial awareness thing sorted. I knew my way around the village. I had been wrong before though, at Christmas, Santa came to the Woollies Grotto and I remembered quite distinctly how to get there. It was in the snowy area outside of a small cave toward the back of the store. You had to wait your turn and then cross over a small hump bridge, over a frozen pond with penguins and elves, before sitting on the bearded man’s knee and telling him that you wanted a train set. Later, after Christmas, I wanted to visit him again, mostly to tell him about the apparent mix up with the presents. I ran to the back of the shop, my wheezing Gran in hot pursuit, only to find nothing. Where I expected to find the grotto, now there was no cave, and no humpback bridge, just a selection of light fittings; from which I was promptly pulled away.

Of course, now I understand that it was just a display, specially erected to draw customers, but to this day, I have no such explanation for the bridge. The next nearest bridge was two miles down the line, near enough to see the tops of wagons go over, but you’d need a hefty set of binoculars to spot someone waving.

Until just a few days ago, I’d put this one down to false memory, or an overactive imagination. But Carmel had started researching our family tree, now that we had started a family of our own, and we’d agreed that we would put aside a copy of the local paper from the day of Byron’s birth; but as a nice surprise, I ordered reprints of the Chronicle from the days that me and the wife were born.

On page eight of the Dearne Chronicle, 22 August 1974, there was an article about the planned demolition of the unsafe Spur Lane Bridge as it was structurally unsound. It went on to say that the Vickers family, whose son had tragically fallen from the bridge in December the year before, were leaving the area to start a new life with their two remaining daughters.

Make of this what you will, I like to think that my feet are firmly on the ground, but in the delivery suite, when Byron took his first good discerning look at his new world, the midwife looked over and smilingly said, “This one’s been here before”. I knew exactly what she meant.