It’s over two months now since I learned of the passing of a childhood friend, and although he would probably call me a daft bastard for this I felt I should pay some tribute, in some small way.

It is what it is.

Things of interest, travel, transport, nostalgia and history, speculations and musings…

It’s over two months now since I learned of the passing of a childhood friend, and although he would probably call me a daft bastard for this I felt I should pay some tribute, in some small way.

It is what it is.

We are at an age where a new technology has come along. AI is making headlines as it infiltrates our daily lives. It is, apparently, writing successful job applications and essays. It threatens to flood the blognet with regurgitated drivel, so naturally I’m curious.

I have, admittedly, wasted an hour or two exploring the free image generators with mixed results. The AI generated images aren’t displeasing, but they also aren’t anything either. They are a curiosity, and have some illustrative utility, but there’s no value in anything that can be generated in a second on a whim.

But I wanted to see if there was much to the hype. Could it be a shortcut for my own endeavours? Word on the street is that Self Publishers are flooding Amazon with AI generated novels. How can that be good?

A test was necessary. On my massive to-do list is a reflective history of my home village. I have collected hundreds of accounts and memories from social media, news clippings, old photos, and read several books written about the place. There is still more to do, I might never finish it, but this is more about the journey I suppose, and I’m enjoying it so far.

But anyway. Could AI clip a few years off of my local history writing journey? I decided to ask it a whimsical essay question.

Write an essay explaining the socio economic situation in Thurnscoe South Yorkshire, describing its history, people, industry, culture, and future prospects.

Thurnscoe South Yorkshire is a deprived inner city area in the metropolitan county of South Yorkshire, England. It is located approx 12 miles north of Sheffield and comprises the following wards: Burton, Clay Cross, East Pinder, Heppelthorpe, Jarrow, Mexborough, newington, and thurnscoe. The 2001 census recorded the population of Thurnscoe as 9,507, a decrease of 2.1% from the 10,047 recorded in 1991.

The socio-economic condition of Thurnscoe is reflective of the UK as a whole. Poverty, lack of opportunities and poor housing are common features. Thurnscoe has seen little recent job or economic growth, and its industry is aging and in decline. There is a high level of social deprivation.

Nevertheless there are also some positive features. The community is fiercely proud of its history and there is a strong sense of community spirit. The people are friendly and hospitable, and there is a lot of involvement in voluntary and community activities. The sense of humour is often unforced and the local pubs and clubs are lively and lively places.

Thurnscoe is unlikely to experience any dramatic socio-economic changes in the near future, but its prospects are difficult to predict.

An essay is a composition of prose that addresses a particular question or topic. It can be long or shorter, formal or informal, comprehensive or specific, and it typically explores one or more ideas in depth.

As starting points go, this is pretty poor. It takes some stratosphericly high data and waffles a bit. This isn’t even GCSE geography level; just to be certain I also asked the AI what an essay was, I would have expected a few thousand words, but no, essays can be short form now, bit convenient. The claim that students, or job applicants, could use this tool as some shortcut to advantage doesn’t hold water. I would need to tweek and customise and furnish it with actual facts and research, in that the ChatGPT interface has nothing on the good old fashioned keyboard.

And perhaps more importantly, you can’t eat AI dessert. Just saying.

Friday 24th February. The return trip from the office, now much less frequent thanks to home working, and I somehow managed to miss the train.

I didn’t miss the train from Baker Street, that wound its way, bouncingly, beneath the streets of London, and never failing to induce a Gerry Rafferty ear worm for at least a couple of stops.

I didn’t miss the train from Euston. I arrived there with ample time to join the hundreds of others craning their necks at the departure board, waiting for the platform number to be announced, before their dash to grab a seat. I definitely didn’t miss the chaos of conflicting commuter stampedes, as the passengers for the Birmingham train, the Manchester train, and Glasgow, all tried to pass through each other, as luggage laden ghosts, and failed.

No. I didn’t miss the 18:30 with its charming passengers. Like the guy that chose to sit with me just long enough to munch through a smelly toasted cheese sandwich, a packet of cheese and onion crisps, demolish a bottle of coke, before moving up the train to another seat, leaving me with the discarded wrappers. Or the delightful extended family of Cumbrians that didn’t think to reserve seats together, and didn’t let the separation of seats hinder their conversations. No, I didn’t miss hearing about how bored they were on their trip back to Carlisle, or how much charge each of them had remaining on their phones.

Nor did I miss my onward connection, there was time enough for a beer or two before I boarded the 21:31 to Skipton, with its loud group of drunks heading back to their homes in the Yorkshire Dales.

The train I missed wasn’t taking me home to my beloved family after a hard day’s grind, it was something altogether more elating, brief as it was.

At Lancaster station there is a pub called the Lock and Tithe, and it’s placement so perfectly aligned with my travel arrangements and proclivities that it’s not unreasonable to suspect divine intervention.

I left my train from London and made a bee line to the bar, ordered a pint of Blonde and a packet of crisps, and seated myself outside. The usual hustle had died down and my previous train had departed onward to Glasgow, but I noticed the platform remained busy. People with cameras were in particular abundance.

“She’s just passed Hest Bank” I heard someone say, and I put it all together. A train of interest was on its way. A train that happened to be the Flying Scotsman, a steam locomotive known throughout the world, and one I have taken the time the view across the country.

This was good news of course. I would delight in the passing of any steam engine, rare things as they are, but as excitement grew, and the spectators readied their cameras, I was gripped, irrationally, by FOMO. Fear Of Missing Out. I readied my camera phone and rose from the bench.

She whistled as she approached the station, and I tracked her through my screen, snapping as she went.

That was the best image I captured, and reviewing the blurred JPGs on my phone screen I realised I had squandered something special. In those minutes respite between obnoxious fellow passengers, the universe had conspired to reward me with a brief spectacle of sound and fire and smoke and joy. And I spent that moment looking at the tiny screen on my phone.

I had missed the train.

I will take this lesson for what it is, a reminder that I, and everyone else for that matter, should do their best to live in the now. Now is all there is and where it’s at. There is nothing on the screen that can convey the anticipation of the people on the platform that had gathered for the event, the thrill of the whistle and the clank of pistons. The feel of the warm air on your face and in your hair, displaced by the mass of speeding steel, and the lingering aroma of coal smoke and oil.

The next time fate brings me to such moments, I will be there to live them, and my camera/phone, can stay in my pocket where it belongs.

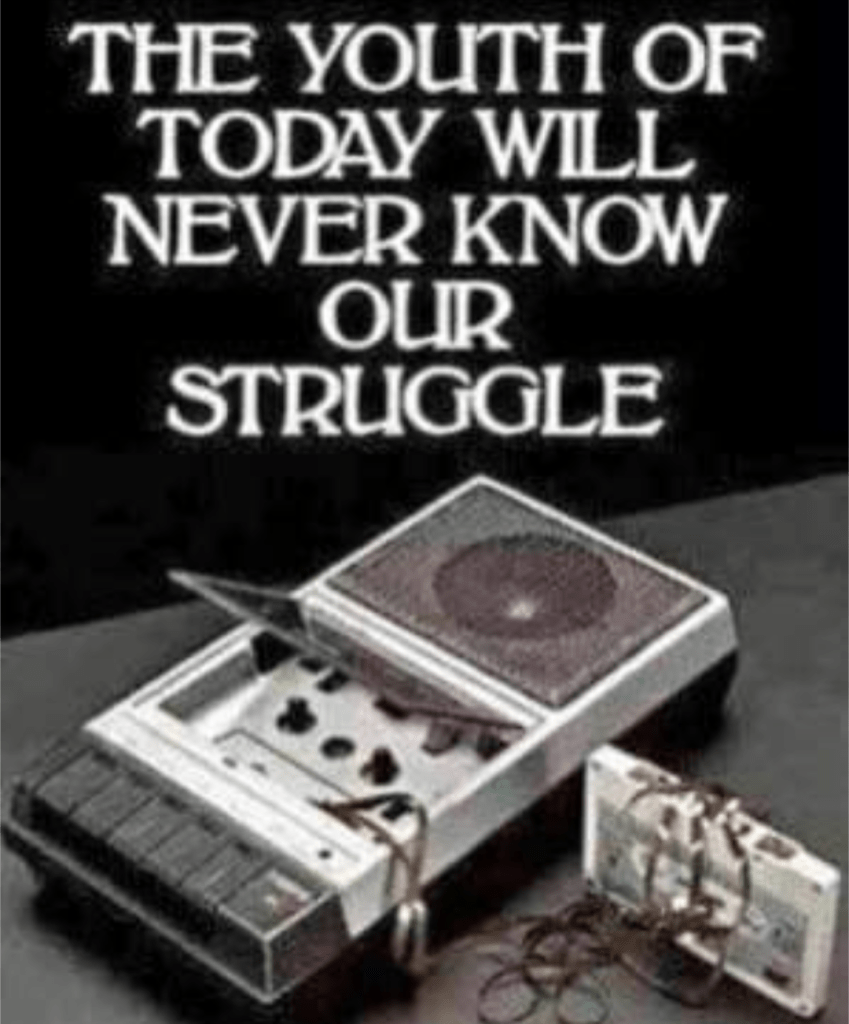

A Facebook meme. I am spending way too much time on Facebook. How much is too much? Some. Some time is too much many might say. But anyway. A meme cropped up.

The image of an old cassette with its tape all mangled and caught up in the tape head mechanism. Yup. How awful that was.

I remember one Christmas, probably 1988, I received a Walkman type device with headphones, and, among other things, Kylie Minogue’s first album, on cassette. That Christmas night I dutifully went to bed when I was told. With the lights out, and me all snug beneath my duvet, I put on the headphones and pressed play. I didn’t even hear the first song in full. “I should be so luc…”

The tape player mangled my brand new Kylie album. And that wasn’t the first and it wasn’t the last. But what could be done? My room was full of cassettes. I had them for music, I had them for computer games, I even had audio books and a beginner’s course in French.

CDs changed that, but they changed a lot more than the mangling of tape and the bother of rewinding. They brought the repeat function, the skip function, and the program function, and that was no bad thing.

I didn’t give it a moment’s thought at the time. I didn’t have to listen to songs I didn’t like, and I could listen to my favourites on repeat, in superior sound quality, and no risk of damage or even wear.

Then came MP3. It became possible to rip your songs from your CDs and play any song at random. Out of the hundreds of songs I’d collected over the years I only ever listened to a handful.

And then streaming came along and you could listen to any song you liked, whenever. Virtually any song ever recorded was now at your finger tips. I occasionally listen to a song or two, maybe every other month, if I feel like it.

Now, this train of thought keeps me going back to a quote from Star Trek:

We believe that when you create a machine to do the work of a man, you take something away from the man.

Star Trek: Insurrection; Sojef to Picard

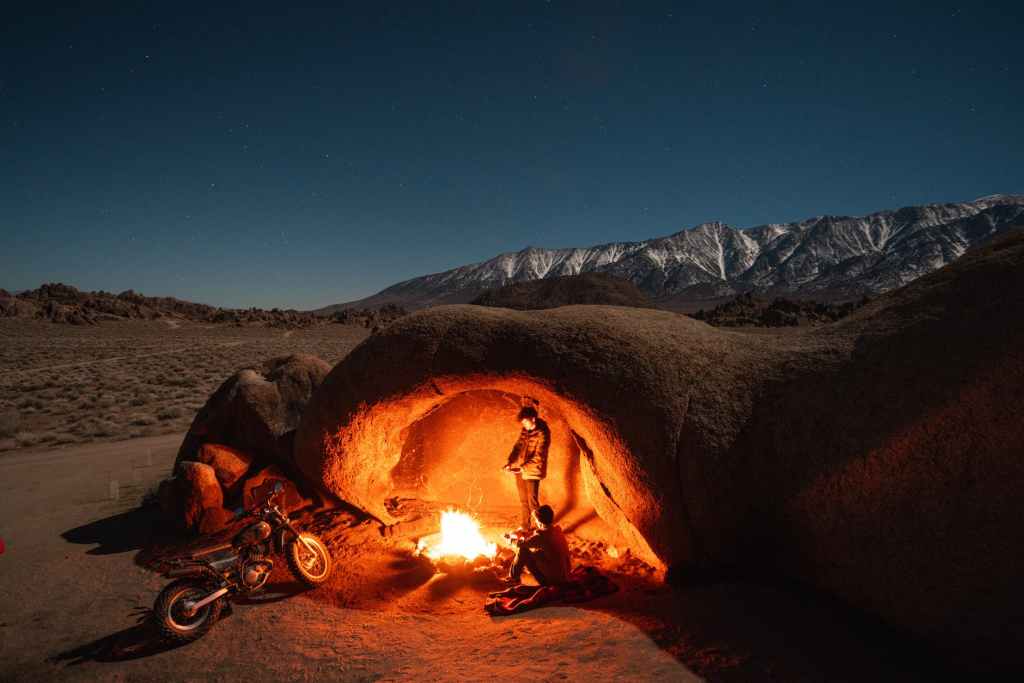

In star trek, a group of people on some distant world had opted not to use their technological prowess because it lessened them, diminished them. I can see how that might work. But I’m not about to start listening to music on cassette again because streaming is too easy. That would be like cooking on an open fire in a wood because a kitchen is too convenient. But isn’t that what camping is?

When I was a teen I caught the bus every day to college. The journey was an hour. In the morning I would listen to Alan Parsons Project’s album Pyramid, on the return journey I would flip the tape and listen to I Robot. Thirty years later, every note in every song connects me immediately to a specific point on the bus route. Conversely, on the rare occasion that retread those ways, I automatically think of the song. Such is the power of the music, and it’s not just the song, it’s the emotions, the fond memories that it evokes. I doubt I’d have that if I’d had an unlimited playlist, or even a skip button. But that’s not all we’ve lost.

It’s not a major thing by any means. I don’t think the youth of today would believe they were missing out on anything. They’ve got their own music, and their own struggles. But this meme came up while I was pondering the nature of bliss. This is a philosophy blog afterall, and I was looking for a way to articulate this theme, that we cannot know bliss unless we know strife.

If a song is just a voice command away, it must surely have less value than a song that is recorded from the radio using a separate audio recorder to radio, speaker to microphone, in a noisy house with annoying siblings. And when the device can destroy your efforts. The song, listening to the song, enjoying the song, is the reward for the effort of simply hearing the song.

It’s a small thing, listening to a song, but it’s also a win. It’s a small win, but it’s an achievement none the less, and the way our brains are wired to give us little chemical rewards, dopamine I believe, when a plan comes together, missing those little wins must surely have some cumulative effect.

I’m not passing judgement on people’s lives, lifestyles, or life choices. We are where we are and what is is what is. A lot of the effort has been removed from our lives and yet we are in the midst of mental health crisis. I think there is a connection and that the struggle was confined to audio tape.

Thanks to Facebook I am exposed to a lot of unhappy people posting about poverty and misery, and sharing memes of their hopes that a communist revolution will resolve all of their problems. They haven’t thought it through. But I also know that there is genuine hardship out there, and that not everyone has an easy ride.

But take food as an example. If you want a pizza you can buy a basic one for 99p from the store. Or you can buy a premium one with stuff crust and generous toppings for £5. Or you can pay about £8 and have one freshly made for you and brought to your home with just a few commands on a smart phone app. I would argue though, that takeaway pizza for £8, though it might have better toppings and higher quality ingredients, it doesn’t have the value of the 99p pizza to the person with only £1.02p in their pocket that has a mile to walk to the store and a mile to walk back, and barely has the funds to cook it. Value comes from the struggle, and the struggle brings reward.

But back to the pizza. You want pizza, you can have pizza, very conveniently and tasty too. Then you have the extra time available because the pizza takes no more effort than sliding into a hot oven and sliding out when it’s done. There’s even a machine to wash the plate for you. Effortless and unrewarding.

Imagine that pizza if there was no supermarket and there was no takeaway. Just a butcher, a green grocer, and general store to buy flour and yeast, meat and veg, and oil, and spices, and if those shops were separated by some notable walking distance, and some produce were in short supply. One might be tempted to not bother with pizza at all, too much effort, have a sandwich instead. The pizza has become unobtainable to some extent and it’s value has increased. It has ceased to be the easy option, it is no longer junk food, it has become an endeavour.

Endeavours involve struggle that leads to reward. This is a tough problem though, and it affects all of us, unless we have a calling to pursue. You might think that making the pizza from scratch might resolve the issue, and although making a pizza from scratch might taste nicer than the store bought variety, the reward isn’t there because the struggle isn’t real. You choose to make pizza the hard way, with readily available ingredients from the supermarket. There might be some reward the first time you make it, that’s the learning reward, but it’s not a struggle, it’s a choice, an indulgence.

More and more of our life is being prepackaged for our convenience. More and more of our jobs are becoming automated. About ten years ago, maybe more, probably more to be honest, I wrote a short story about a shop that had no staff and no check out. You just walked in, took what you needed, and walked out. The shop would know who you are, what you took, and charge your account for it. Those shops exist now. I thought it was a moment of genius foresight and never expected them to become a reality in my lifetime, I never suspected that they were already in development as I wrote my story.

Where does this leave us, as a people? The meaningful work done for us. What then? It’s been suggested that we’ll all need some kind of basic income, but what do we do with that? When our most basic needs are met and our whims catered to. What then?

Maybe Star Trek has the answers.

Star Trek is that bizarre utopian future where everything is taken care of, but they’re on a star ship exploring the universe, so not the same as our situation. I think if I was on a star ship I too wouldn’t be bothered by the coloured food cubes, they’re in space, meeting aliens. There are exceptions though. Commander Riker sees the failings of the replicated food and he tries to cook eggs, but he’s not very good at it.

This is all a long winded way of saying something isn’t right. The youth of today won’t know our struggles, but they have their own. The world is changing. We’re on the cusp of super conductors, cold fusion, quantum computers, abiogenesis, and who knows what else. The world is changing so quickly, but if we don’t find some way to restore purpose to everyone’s life, the struggle of a mangled tape will be a luxury beyond the imaginations of our future generations.

It may be a fad, it may be the algorithms, it may be my settings, I don’t know. But articles about AI are filling my news feeds at the moment, and truth be told, I’m not reading them.

Last night I found myself with the big TV to myself and an unexpected bottle of red I found next to the Christmas decorations that still need putting away. Naturally I embraced this me time to watch three old transport documentaries from the sixties – who wouldn’t?

I won’t labour the details but there was a programme about the newly built and most advanced automated marshalling yard in the world, Tinsley. It closed in 1998.

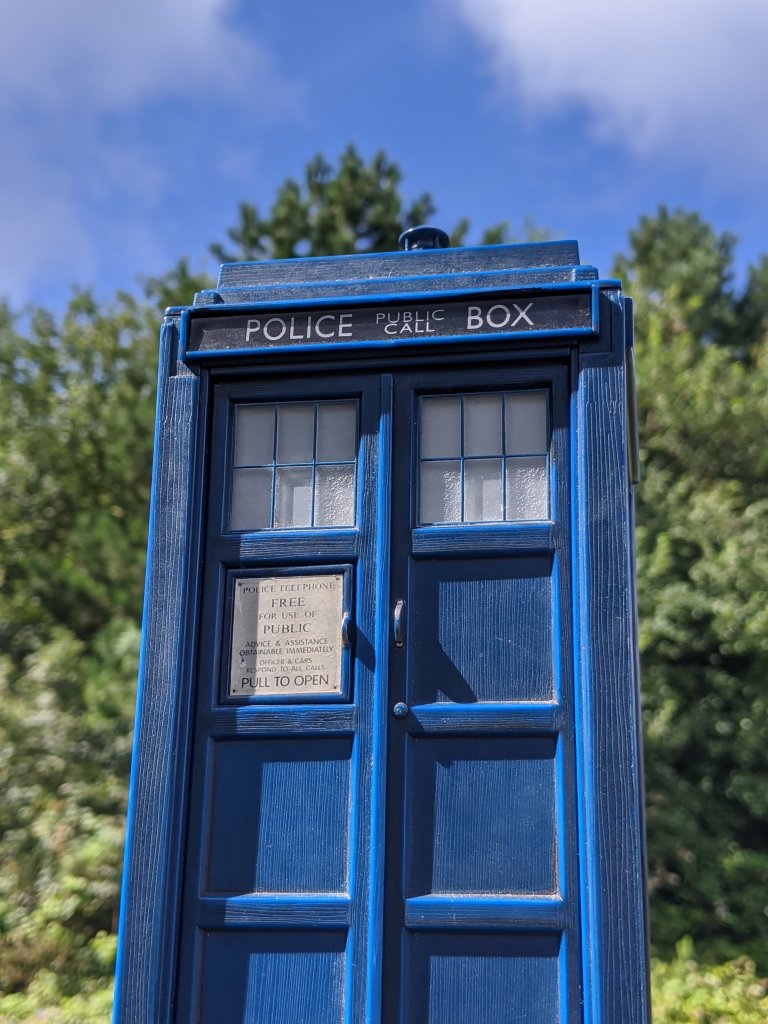

There was another one about the last day of Trams in Sheffield. The rails were ripped from Sheffield’s roads in 1960, and put back in again in 1993.

The last one was a BBC documentary called Engines Must Not Enter the Potato Siding. It was a look at the railways and railwaymen in 1969 and spoke to drivers and crew. Some lamented the passing of the steam engine, others espoused the modern electric locomotives. The electric locomotives, and the line they operated are both long gone. The trains went to scrap, the trackbed grassed over.

But what am I talking about trains for? I like trains. Also. It’s change and it’s impermanence. AI, or creative AI is going to ruffle a lot of feathers, and the world will adjust and move on. Banning AI at university because of the potential for cheating would be like banning the library because of its potential for cheating. AI gives students unlimited and context driven information in a form that their assessments require. It’s the assessments that must change, and will change, and as with everything else, it’s the early adopters, the innovative, that will reap the rewards that this new technology offers.

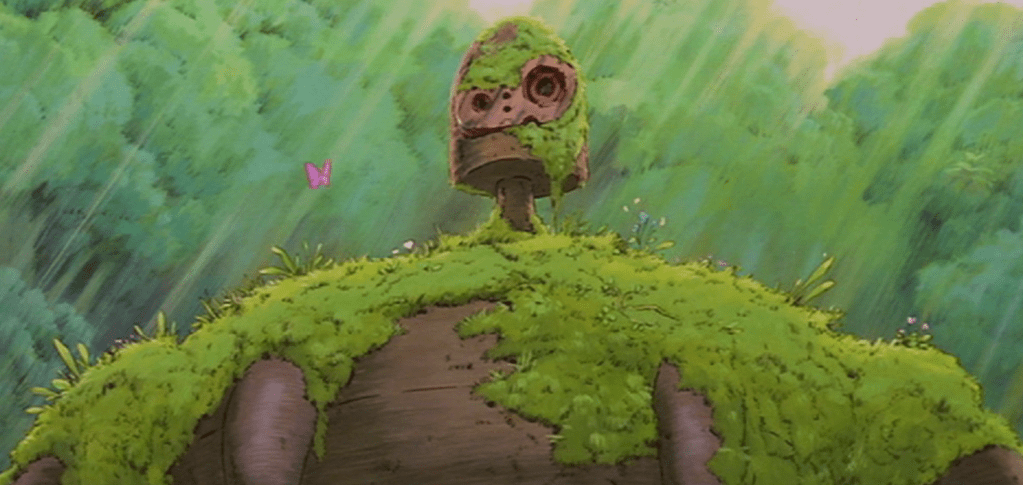

It was a warm spring day in the eighties that I discovered the piece of art that is Ghibli’s Castle in the Sky. I remember it particularly well because my aunty had come round to cut my hair and I ended up missing a good chunk of the movie, but what I remembered of it stuck with me for about twenty years or so until I found the DVD.

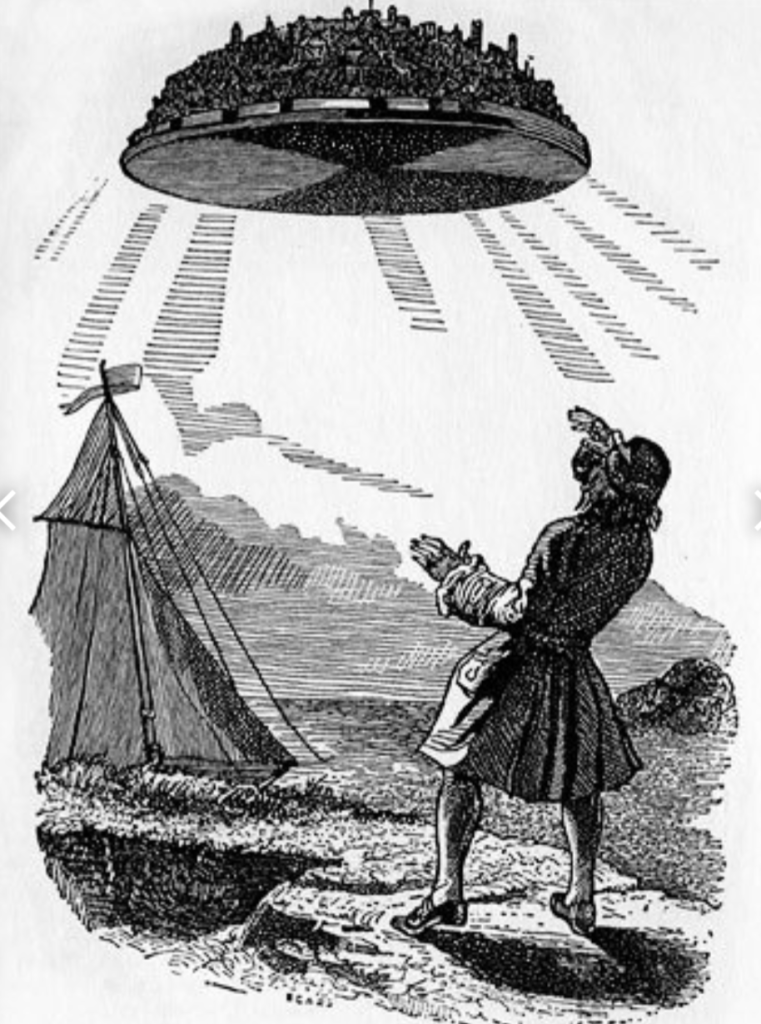

Laputa, Castle in the Sky is an animated movie based loosely on one of the bonkers communities encountered in Jonathan Swift’s classic Gulliver’s Travels. In it, the eponymous Gulliver encounters a madcap people inhabiting a floating castle, directing it with the magnetism of core load stone.

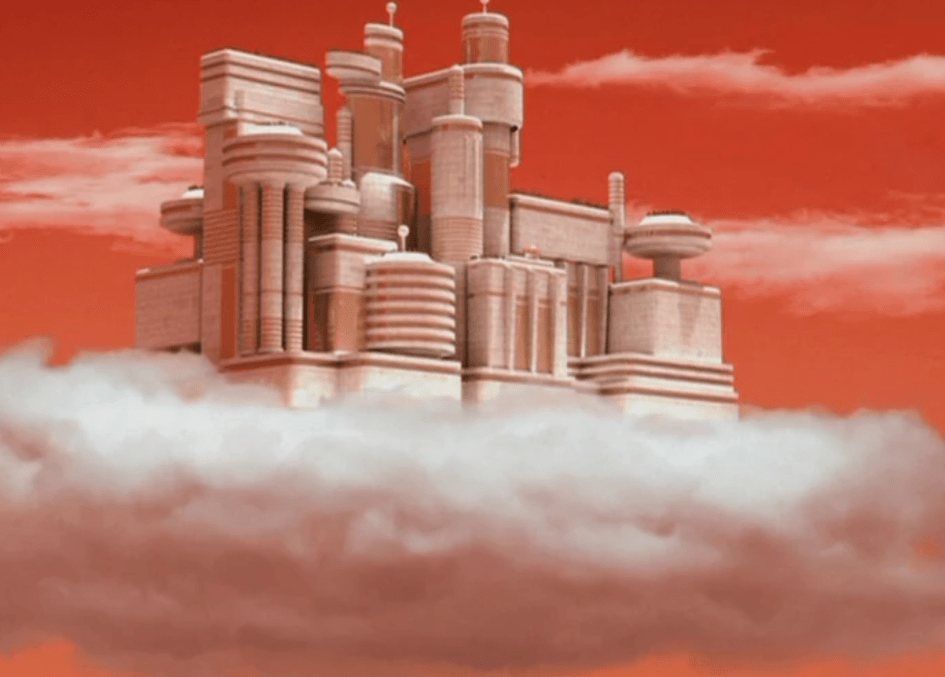

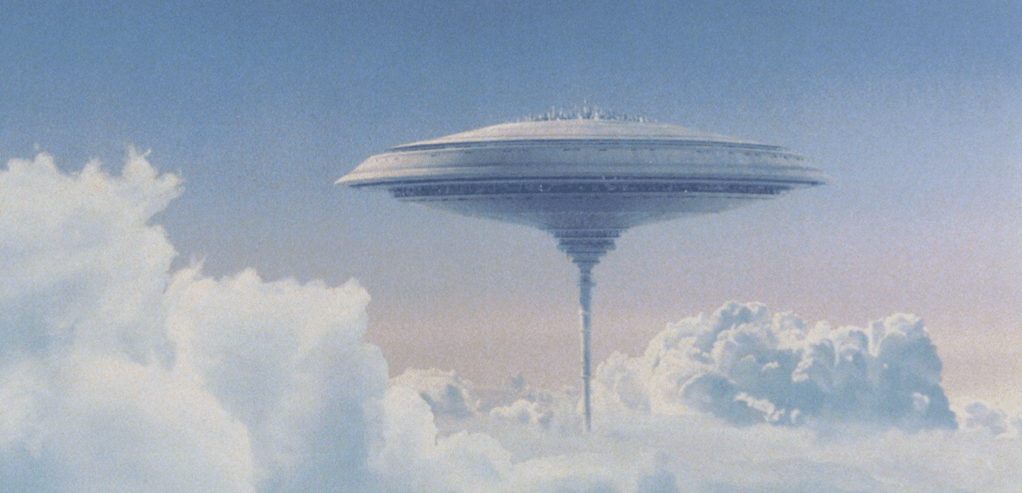

Cloud castles do hold a certain fascination in our civilisation, and they crop up time and time again in both our folk lore, and modern intellectual properties, from Star Trek to Star Wars and everything in between, there are cloud castles or cloud cities.

But fascinating as floating castles are, that isn’t the true appeal of the movie. The location of the story isn’t specified, there is no indication of when this takes place but it feels like the early twentieth century in Europe. Steam power and flat caps, but this isn’t a historical piece. There is powered flight beyond what we have, massive airships and insect inspired winged single seat craft.

When and where this is, we do not know, but there seems to have been a great destructive war and the people that are left are just getting on with it. The backdrop is that of post industrial decline. Crumbling brick buildings, factories, furnaces, mines. It’s a nostalgic post golden-age golden age. That’s the only way I can describe it.

The lives of the characters we meet look tough. What they have is old and broken, they mend and make do, and they work hard to survive in a harsh barren mountainous area. But they laugh and they smile and make the best of it. Except of course for the antagonists. There are forces in this world, above the lower orders, with agendas and schemes that intersect with the sleepy mountain town when a stranger falls out of the sky, and when outsiders arrive in the town to find her, the residents are not to be pushed around.

It’s a golden age of freedom and innocence, of kinship, community, and honest work, but all around there are clues to a golden age of abundance that has since been lost, the mythical floating island, and their terrible weapons of war, the mysterious giant robots that are dotted around the countryside, rusting, overgrown, returning to the Earth.

There is something both alluring and distantly familiar about the world presented here. I’m reminded of the eighties, when the mines closed, and the steel works, and the factories were left to decay and collapse, the dismantled railways overgrown, like the giant robots, and left to return to nature.

There is something unsettling about living in this age of uncertain abundance. That saying, “easy come easy go”, it is usually said so casually by some vagabond or scrounger type character, but it’s actually a warning. That which we gain with ease, we can lose with ease. I can’t deny the convenience of being able to go to the supermarket and buying an oven ready chicken, but I’m entirely reliant on others, a chain of others, to ensure that there is a chicken there for me to buy. That situation seems way more precarious than the self reliance of a small community living atop a literal precipice. The image of self reliance against adversity is as compelling as it is romantic.

I can’t help but feel that there is a message in this movie, that we have perhaps missed something. A great civilisation of massive power and achievements has crumbled away, and no one remembers it, no one mourns it or even speaks its name, and no one seems the worse for it. That is not to say I’d like to see a collapse of our civilisation, by any means, but a bit more self reliance would do us all the world of good, but I worry we’ve lost the capacity for that. Can’t exactly keep chickens in a one bedroom flat, but I suppose that’s what is romantic about it, it’s unrealistic.

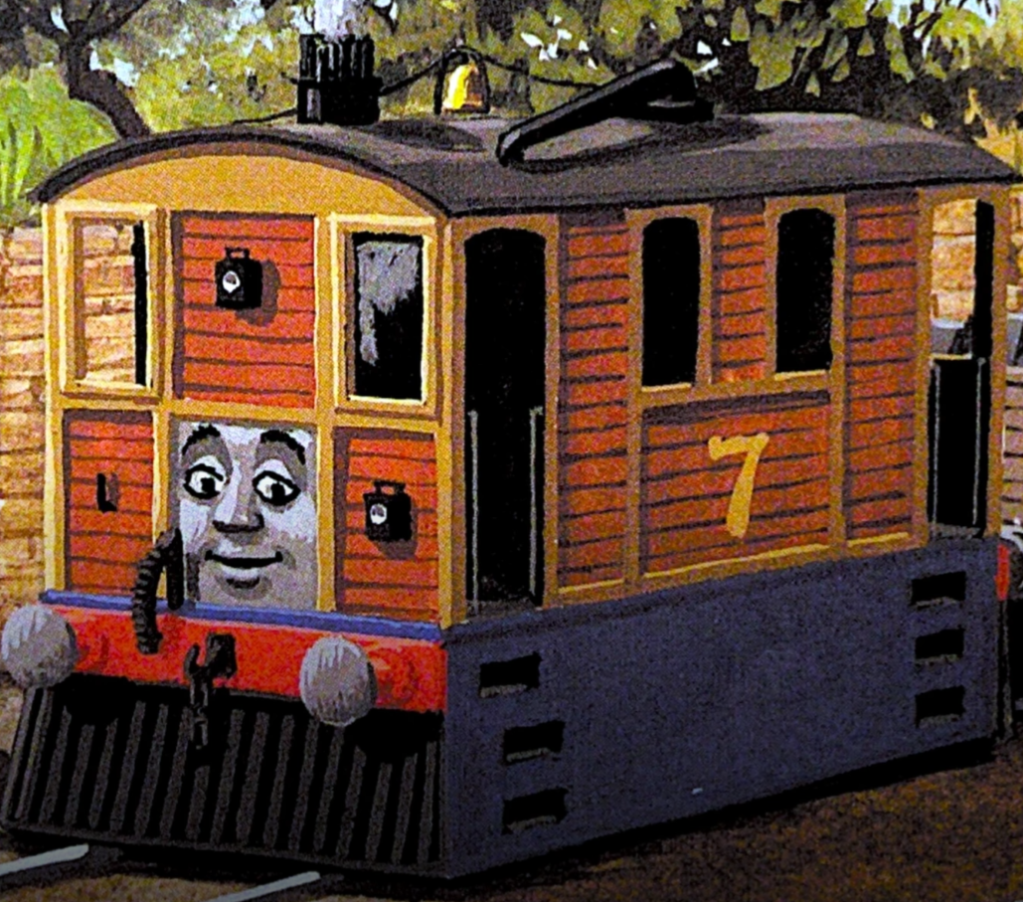

I can’t end this post without mentioning the trains though. There is a wonderful steam railway running through the mountains, carrying coals and wares, and of course the military for its unknown manoeuvres. I can’t help but notice the similarity of the locomotive number 7, to another number 7. Someone once said that there is no such thing as a coincidence, only the illusion of coincidence.

What do you want for Christmas? Dunno.

What do you want for dinner? Dunno, with chips.

What do you want?

It’s not an easy question to answer. I thought I knew what I wanted. I mean, something like that should be autonomic really, shouldn’t it? I mean, the heart wants what the heart wants does it not?

When I was a child I wanted an Advanced Passenger Train for my model railway. I wanted all of the Transformers and Gobots. I wanted lots of chocolate. I wanted to play video games, make video games even. I wanted to climb tall trees and explore derelict buildings.

As I got older I wanted beer, and women, and more beer. Usual stuff really. I wanted a career, a home, a family, a wife, a car, and maybe a little bit more beer.

As you get older, I suppose that question gets more difficult to answer. At first I thought that it was depression. Then I thought it was a midlife crisis and all I needed to do was buy a sports car. And then I thought it was depression again, so I turned to Google for the answer.

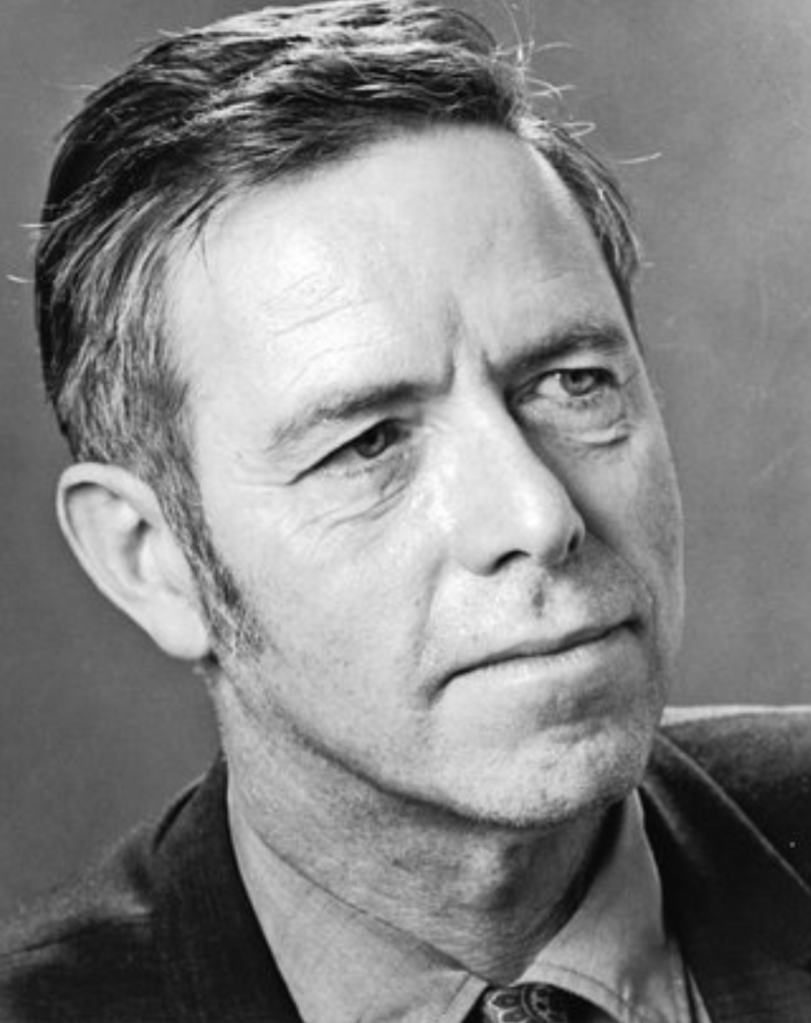

“Why don’t I know what I want?” I keyed into the search box. I reasoned someone somewhere was bound to have figured it out. The first result that caught my eye was a video by a chap called Alan Watts. I didn’t know the name but I recognised the voice immediately from the Cunard cruise ship advert that is doing the rounds at the moment.

I listened to the mesmerising voice of this English philosopher as he got straight to the point. What I heard was an eye opener, though it’s probably common sense to the more enlightened among us, my mind was blown.

When we don’t know what we want we have reached a state of desirelessness. He explains, more eloquently than I could dream, that there are three stages of not knowing. At the start, we don’t know because we haven’t thought about it. Then there’s the stage where were asked, pressed, on the matter, you want this and that, right? And we might say yes, to begin with. But then we realise that no, that’s not what we want at all. Maybe those things will be satisfying for a while, and that we wouldn’t turn our noses up at them, but really, they’re not what we want.

There are two reasons, he explains, why we don’t know what we want. The first one is that we already have it. The second is that we don’t know ourselves.

The question “who are you?” is the same as “What do you want?” I always thought of them as being diametric opposites, but that’s because I was for many years obsessed with Babylon 5.

We cannot know ourselves, if I’m understanding this correctly, because the Godhead cannot be the object of its own knowledge. It is a mystery.

I don’t know, uttered in the infinite interior of the spirit is the same as I Love, I let go, I don’t try to force or control. It’s the same thing as humility.

Upanishad said, if you think you understand Brahman, you do not understand and have yet to be instructed further. If you think that you do not know Brahman, then you truly understand, for the Brahman is unknown to those who know it and known to those who know it not.

Alan Watts

These are powerful evocative words and gave me much to think about.

He goes on to explain that when we give up control we have access to power that we can be trusted with and are one with the divine, but when we try to control our situation, we lose that energy because we are defending ourselves against that which we cannot defend.

We have to give it away and trust the universe because there is nothing to hold on to anyway. Everything is falling apart. We are going to die and leave not a rack behind. What we truly want is kind of irrelevant in the grand scheme of impermanence.

He goes on to quote Shakespeare, a few lines I was familiar with from Star Trek VI, but had never grasped the significance.

Our revels now are ended.

These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp'd towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

William Shakespeare

From The Tempest, Act 4 Scene 1

Everything I recall ever wanting was for a future fulfilled, or a past revisited. But there is no past and there is no future. There is no time. There is only now. The infinite and eternal now. It is always now. Sufficient to the day is the worry of it. They should teach this stuff at school.

"Time is a tool you can hang on the wall, you can wear it on your wrist.

The past is far behind us, the future doesn't exist."

My youngest son spoke those timely words, seemingly out of nowhere, after a long car journey on which I’d considered the matter of time and the eternal now. It’s from a YouTube channel called Don’t Hug Me I’m scared. Deep stuff.

I am a long way from satori, but I did have to laugh on that journey as I mulled over and over the unknowableness of the Brahman. If to know it is to not not know it, and to not know it, is to truly know it, then doesn’t knowing that I don’t know it mean that I do know it, except that I can’t because knowing that I know it because I don’t know it means that I can’t know it because I know that I don’t know it.

Bonkers. All of it.

I still don’t know what I truly want, but I do now know that I don’t know what I want.

You know that feeling you get when something doesn’t ring true? I’ve been getting this a lot lately and I’m almost embarrassed to mention it in case I be carted off to the loonie bin.

There are certain indisputable facts on which all can agree. Such as modern Humans, people just like us, having existed well in excess 200,000 years, closer to 300 with more recent discoveries. We also know from the evidence available that the last ice age ended about 12000 years ago, abruptly, and with catastrophic sea level rise.

History doesn’t have much to say about the ice age because there are no written records of it, but stories of massive destructive floods have been passed down through oral tradition, but because no one thought to write it down at the time they can be easily dismissed as myth, campfire stories invented to entertain the tribefolk in the long winter months or something.

So the story goes, that modern humans, homo sapiens, appeared on earth about 300,000 years ago, give or take, and lived a hunter gatherer lifestyle for about 294,000 years, give or take, until about 6000 years ago, when there was a spark of creative genius and they invented religion, agriculture, writing, and architecture, practically over night. At this time they built massive structures, way beyond our capability to explain, nevermind replicate, all over the world, and then forgot how to do it.

These people were very clever but they had not yet fully understood the importance of documenting all of their developments.

So we know that writing was invented 6000 years ago because that’s how old the oldest discovered writing is. People wrote on stone tablets because they had not yet invented paper, which is lucky because stone tablets have a greater longevity than parchment.

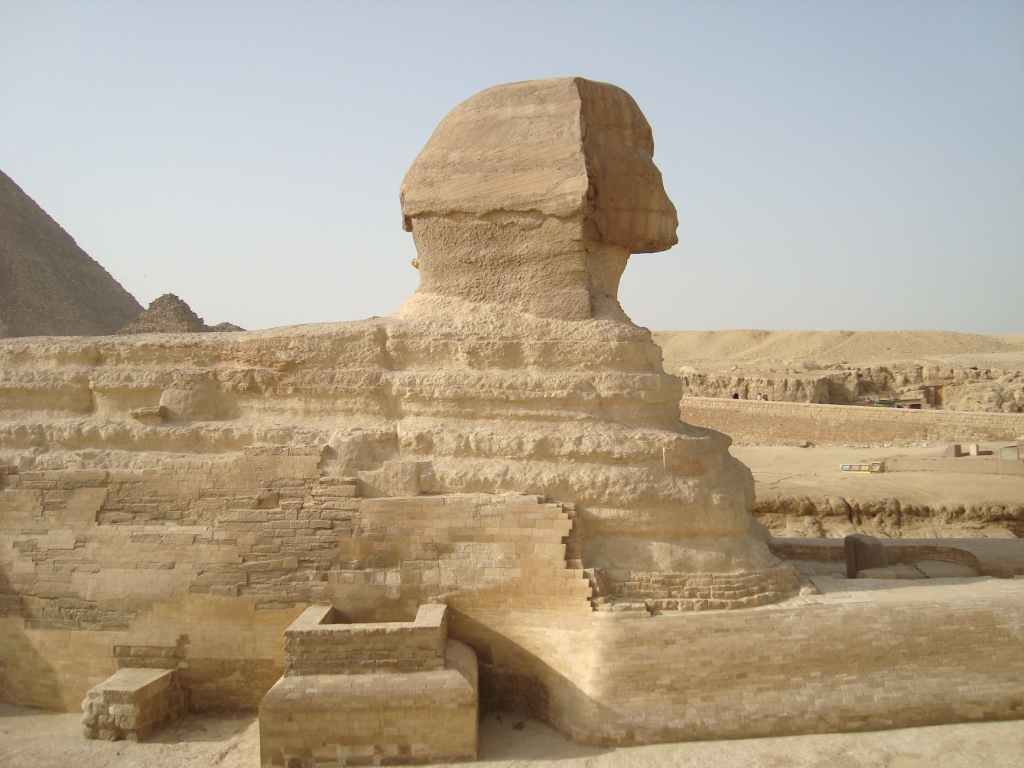

But this is where I struggle. The pyramids are an iconic mystery but their origin doesn’t seem to be up for debate even though the evidence is tenuous at best. There is a bit of graffiti inside the great pyramid that bears the name Khufu, and that is the only tangible thing that can be used, without it, there is no connection to the Ancient Egyptians apart from them being present in ancient Egypt.

The Pyramids are one thing, but the Sphinx was also supposed to be built around the same time, even though it’s clearly weathered by thousands of years of precipitation. I live in North West England, I know what water erosion looks like.

The general insinuation when you don’t readily believe that a statue carved out of solid rock in a desert can show signs of extensive water erosion is that you must be some kind of deviant.

“Well if the ancient Egyptians didn’t build the pyramids, who did? Aliens?”

It’s a hell of a stretch isn’t it? Accept their story, in the face of everything else you know, or get called a name. I don’t have any skin in this game, it’s fascinating to me, but if it doesn’t ring true, I can’t help but ask questions, it’s not my fault the evidence isn’t there.

All in all, I find it baffling that the cataclysm at the end of the ice age doesn’t factor more prominently into human prehistory. What’s more plausible? That humans sat on their hands for 300,000 years, and, at the last minute, and in isolated pockets across the globe, made astonishing leaps forward, beyond what we can fathom today, and then forgot. Or that Humans didn’t take 300,000 years to get their act together, and that by the end of the ice age they were doing rather well for themselves.

Anyone that has a lawn to maintain knows how quickly nature takes back any square centimetre that goes unattended. My garden shed is thirty years old and is rotting away. Soon there will be nothing left of it.

Forty years ago, when I was a young scally exploring my village, I felt the world was permanent. That everything was the way it always was, and I’d be amazed when parents told me about the olden days. I had no idea that my home was only a few years old, and I definitely had no idea that it too would be bulldozed just 20 years later, gone without a trace and replaced with more modern houses. The place is unrecognisable.

Back then I would play on a disused railway. The track was long gone and bridges were filled in. The cuttings themselves have been filled in since and the land returned to agriculture. The only trace of the railway ever existing is now in the maps, and a rough edge that can be seen by lidar.

These substantial changes in a small area happened within my own lifetime. What would remain after thousands of years? And what would survive the cataclysms? Ten million square miles of low lying fertile land was flooded at the end of the ice age. Who knows what went under the waves.

I don’t care either way, I just want a satisfactory explanation, and there are so many questions being ignored because they don’t fit. The experts appear to get cross when anyone says ‘but what about..?’. Doesn’t seem very professional.

Either way, I suppose that, in the end, time will tell.

AI is coming so it seems, if it’s not already here.

Computers have been driving trains and landing planes for some time, but now it’s writing novels and drawing some stunning pictures. It’s scary stuff.

There was a particularly downbeat item in the Spectator about it the other day, the End of Writing it said. Now, have no doubt that before long we’ll be able to go to our TV and tell it that we want to watch a Batman v Iron Man movie in the style of Studio Ghibli, and it will be a great film. But I don’t think it’s the end of writing.

For a start, I write because I have something to say. I want to share my thoughts and insights with anyone that will listen. If I was the last surviving human, living in a cave on a planet at the other side of the cosmos, with zero chance of being found by another being, I would still write. AI wouldn’t. AI will fulfil a request against supplied parameters, it will make connections based on algorithms based on existing work and it will compile them in a way that satisfies a user requirement.

If you keep getting exactly what you want, you soon stop wanting it, because it’s there, and you can have it whenever, so it loses its value.

Sure, AI can answer questions and present information very effectively, but that’s not creative. I see AI, in this context, as a development of the audio visual interface. Like the difference between text based output and graphics.

For all I know, AI will set itself the task of tugging on every loose thread and unpicking the fabric of reality, thus answering all of the questions and handing us the moon on a stick, though I can’t help but think of the Nine Billion Names for God whenever computers are put to the ultimate question.

It could happen though, five years from now the AI could have figured it all out and set us on the path toward a Kardishev Type 10 civilization before the end of the decade. I’m not ruling anything out, but if that’s the case, worrying about writing career options is a little redundant.

My point is that although this is coming, I think readers will still want to connect with other humans. Humans will continue to write what they feel, and others will want to read that, and I think that will go on indefinitely.

It is impossible to predict where AI will take us, and where we will take AI. I imagine it will be misused. 1984 gave us the perfect application for such technology, and don’t think we have much defence against it. What will be will be, and I will continue to write about it all the same.

I haven’t posted anything in ages it seems. It’s not that I haven’t had much to say, I always have much to say about one thing or another, but I’ve been distracted by the seemingly full time job of moving house.

That task is now coming toward a conclusion and I have finally begun to unpack some of the things I have spent the past twenty years packing for this very move.

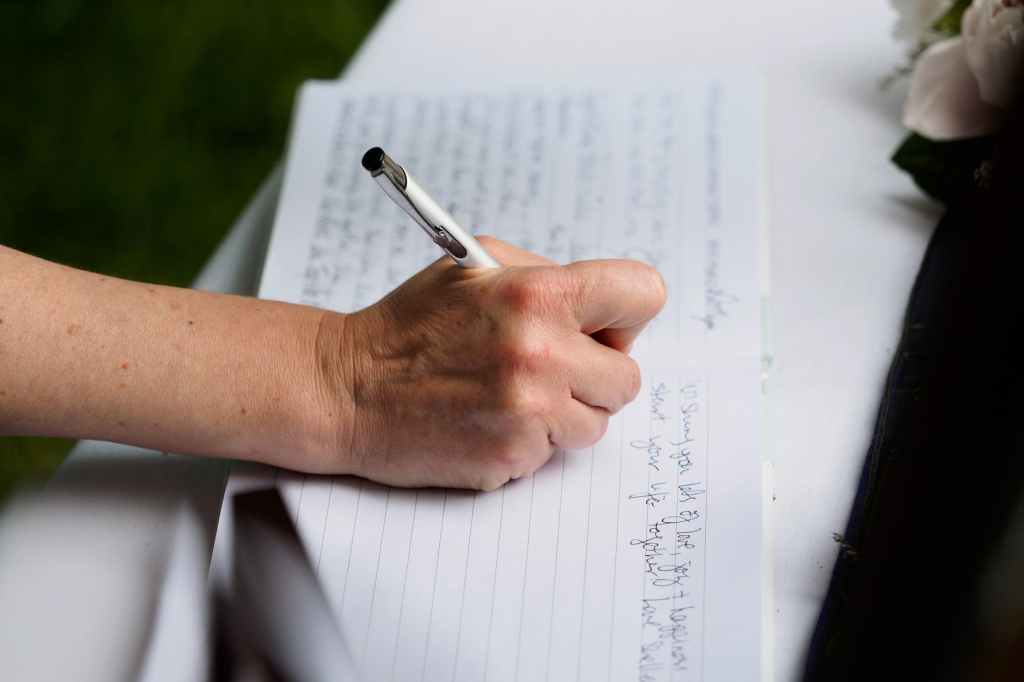

Like most wannabe creatives I have dozens, if not hundreds of note books stuffed with award winning ideas, scribbles, doodles, and sentence fragments written, barely legible, in faded biro on scraps of paper; betting slips, truth be told.

But taking a break from unpacking I decided to flick through the leaves of an old sketch pad, and that gave me an idea for something to do while I waited for my back to un-seize so that I can peel myself from the floor. I could post some doodles.

I don’t remember drawing this hutch, but the caption in the sketch pad tells me it was to do with an abandoned plot device. I’d like to elaborate but there’s still mileage in that device and I will come to revisit it.

Bizarrely, maybe somewhat bizarrely, we now have a hutch much like this in the backyard. Inhabited not by bunnies, we use it for barbecue equipment and accoutrements.

Many years ago, our youngest child, who had just turned one at the time, had an imaginary friend called Foster. Foster usually stood in the corner where only he could see him, and we’d often hear half of a conversation late at night over the baby monitor.

This is how I imagined Foster to look, had he appeared in our bedroom doorway.

This guy has a third eye, and that’s pretty much all I know about him, except that he has a similar taste in sweaters, and better teeth than me. There is a story behind this chap, but I’ve no idea what it is. I’m sure it will come back to me eventually.